Someone is always doing the work.

Against my better judgement, some thoughts on a certain bot. Also chocolate.

Panic is almost always unhelpful, even when there’s a lot to worry about. A lot of the essays about this certain bot all the profs are talking about feel like essays students write at the last minute, and we all know what those look like. (Panic is usually why students plagiarize in the first place, and it will be the main reason why they use the bot.)

I’m not an expert on technology or deskilling, but if all the critical thinking we say we believe in is worth a hill of beans in this crazy world, it’s probably worth taking a step back from our freakout to think about how these dynamics are at play. Here’s a problem that’s in our lives, that we didn’t ask for, what can we learn about the world to understand our problem better? That’s what we ask our students to do, but we’re often unwilling to do it if it’s “not our field,” forgetting that we’re asking students to care, and that the whole world is “not their field,” in the way that we mean it. So, as a non-expert who nonetheless has read a lot of critical literature on work and taught writing-based classes for twenty years, long enough to watch more than a few hype cycles come and go, here are few of the things I keep coming back to.

There’s always someone doing the work.

Always. If things were really arranged so that technology took over, we’d be working shorter days and less panicked and so have more time to write careful rather than panicked thoughts about this topic. I’m only writing this because I’m on sabbatical. It’s almost never about replacing people with robots, it’s almost always about bosses using technology to exert more control, to make us think our skills are outdated and mean nothing, to subject us to more rote work and surveillance, discipline our labor, and make us ignore the conditions of the people who are always doing the work, as Vice recently reported: “Tech companies regularly hire tens of thousands of gig workers to maintain the illusion that their AI tools are fully functioning and self-sufficient, when, in reality, they still rely on a great number of human moderation and development.”

That quote comes from an article about how the algorithm we’re panicking about paid Kenyan workers $2/hour to improve it since earlier versions “often produced sexist, violent, and racist text because the model was trained on a dataset that was scraped from billions of internet pages.” There are two important things to notice about this, one about the nature of the product and one about how it works. First, the product.

It’s a product.

It’s not a technology, it’s a product made by a for-profit company (with a non-profit arm that’s doubtless good for publicity and tax purposes) with a name that’s designed to trick you into thinking it’s all non-profit, or open-sourced. The way most of us are writing about it amounts to hyping a product. It’s free for now, but for how long? Dealers always give you the first taste for free. How long before it has sponsored ads and content in it, the way google and social media have much more of than they used to? If we’re critical thinkers defending the written word, we should know what this song sounds like. As professors we go right into the “do we have to use this technology” discussion without thinking about what it means to accept a product into our lives that was made by billionaires or wanna-be billionaires who do not have our interests at heart.

I suppose I’m being annoyingly coy, by not calling it by name, like some cut-rate Patricia Lockwood, but filling our feeds and typing fingers with its name, talking about how good it is, even calling it an “AI” just feels like unpaid advertising. One of the first things that came to mind when the freakout started was the phrase “Udacity.” It came to mind like Steffie whispering “Toyota Celica”, and like Steffie’s poor father it took me a while to place it. Do you remember Udacity? Maybe EdEx? Funny how we don’t since ten years ago we were all going to be working for them in ten years and if we didn’t get with the program, to the dustbin with us. This is different of course, and I’m not saying we should just mutter “this too shall pass,” but maybe a little humility and reality check to this all, a little skepticism in the reporting. And for the record, muttering “this too shall pass” is actually a very good response to a lot of educational fads and administrative initiatives.

The algorithm is on a continuum with current plagiarism tools.

The other thing the Vice story reminds us is that while using this algorithm is not the same as cutting and pasting from wikipedia or, more likely, the first google hit, the difference is one of degree not kind, since what the algorithm does is reshuffle existing language, not create it. And, just like with the underemployed ex-grad students who write essays for money (subject of another periodic and soon forgotten faculty freak-out), there’s always someone doing the work. On some level, it’s not surprising to see that not only does the algorithm mimic plagiarism, in many cases they are plagiarism.

Don’t Panic Doesn’t Mean Don’t Worry, and If You’re Worrying It Doesn’t Mean You’re a Bad, Uninspired Teacher.

To say we shouldn’t uncritically echo hype is not to say that professors are wrong to be worried about this, or shouldn’t think about it at all. To figure out how to worry without panicking, I think it’s important to slow down and figure out the nature of the problem. Does it bother us only as a cheating issue? Or, do we think that if a bot can do something, it’s not worth doing? It’s not an obvious question. Computers have been able to beat anyone at chess for a long time (“How would you beat a computer,” the grandmaster was asked. “Bring a hammer”), but we still find it useful - or pleasurable, or valuable on some level, to learn to play chess. Kids still learn math that can be done on calculators, but they also spend less time on long division than we did, which seems ok.

There’s an impulse in progressive pedagogy to say that if your assignment can be easily plagiarized (or now, written by the algorithm), it’s a bad assignment. I’m sympathetic to that, and I do think it’s useful to think about plagiarism-proof assignments. Interview a family member, do an ethnography of your neighborhood, all that good stuff. But there are certain things like summarizing that are valuable to do, even though algorithms can now do them, like it’s still valuable to play chess and learn arithmetic. I think there are ways to think about how classrooms can help us preserve that, maybe by doing these assignments in a different way, and thinking about that is not necessarily “punitive.” (But any startups selling detection software to solve the problem they are creating can get bent). At the end of the day, there just isn’t an alternative to having relationships, believing what we do has value, trying to convey that value by example. For what this looks like in practice, you can’t do better than John Warner. Given what I say about summaries, though, I think the important thing to remember is it can’t kill anything worth doing not because anything it can do is not worth doing, but because if we believe it has value to the doer, than the problem of an algorithm that can do it is practical, not existential - how to get the doer engaged so that they experience that value. Which has always been the challenge.

Mrs. B.

When I was in high school, I had a favorite English teacher, Mrs. B. We were studying Shakespeare’s sonnets and I wrote her a “proposal” for my essay, saying I would use my experience as a “non-beautiful” person to write about his descriptions of beauty. Bless her, Mrs. B. ignored everything else and just wrote “what do you mean” in the margins next to that. Needless to say I don’t remember what I went on to write about the sonnets but I do remember that she wrote that in the margin. This may or may not have anything to do with the purpose of writing and the purpose of teachers.

Chocolate

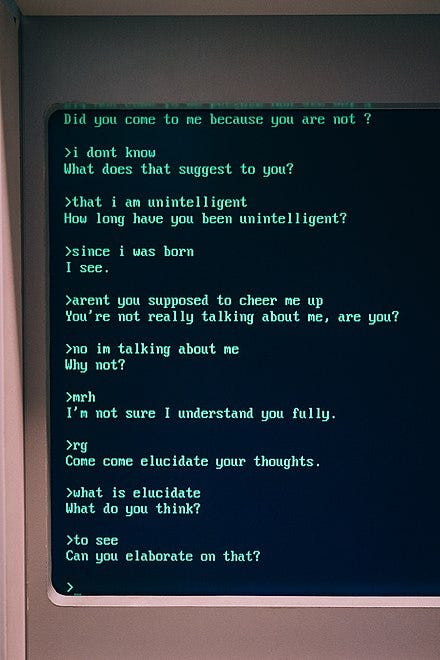

Returning to hype for a minute, a cliche of technology writing is the “was it ever thus” gesture - so it’s interesting to me that this has seemed largely absent from this cycle. Josh told me the first thing the discussion made him think of was the ELIZA chatbot which was released in 1966 (!) and spooked people by its ability to fool people into thinking they were talking to a human. Looking back it’s easy to make fun of its bad therapy-speak and wonder how people could be fooled. A more interesting way to look at it, I think, is to wonder this says about the quality of conversation the fooled had been having that made this seem a good substitute.

I recently wrote about a biography of Kathy Acker, one of the pomo writers I loved in the 90s who had a utopian view about cyberculture as an interactive place of play. When I think about all the theory and pomo I read in the nineties and what was valuable about it, I often think about the sentence: “You don’t use language, language uses you.” It’s useful for all of us to think about: when we start shadowboxing on some other “platform”: we have met the algorithm and the algorithm is us.

As for me, when I think about retro images about computers taking over, the early memory that comes to mind is the guy in the Willy Wonka movie who tries to bribe a computer to find the golden ticket for him, promising a lifetime supply of chocolate. “And what would a computer do with a lifetime supply of chocolate” the computer asks, something I thought was hilarious when I was a kid. If they find algorithms that start eating my chocolate, then I will definitely start to panic.

Also “At the end of the day, there just isn’t an alternative to having relationships, believing what we do has value, trying to convey that value by example.”

YES.