I wrote most of this last week as my semester and the kid’s school year wrapped up; as it happens, I’m getting it to you wonderful folks two days after Zohran’s amazing victory. Something about trying to do any journal-style writing these days is that as soon as you write something it feels outdated - how lovely to have woken to the thought this may have felt too grim for the day!

My Zohran story is that the he came to the college where I work to speak in 2018 or 2019 I think - before he had even become a candidate for State Assembly. One thing he told students is that even if you’re not a citizen and can’t vote, you can knock doors. Wish I’d gotten a picture!

On Wednesday I congratulated a young woman with Zohran bandana, which you could only get by volunteering. “Happy Zohran Day!” she said as I got off the train. I was getting texts from friends the way you usually do when it’s your birthday or something bad happens. It was nice to have it happen this way.

Like everyone, I have thoughts about NYC politics and I think I’m involved enough that they’re not totally worthless but while takes aren’t as unbearable after a win as after a defeat there are still enough of them to go around, so I’ll just wish you all a happy Zohran week before sharing this post. I believe that we will win.

* ******************************************************************************************************

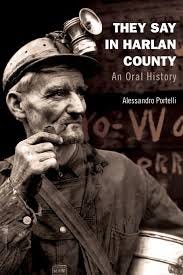

On the last regular day of one of my classes this semester, I showed them the classic labor documentary Harlan County, USA. We also read part of They Say in Harlan County, an oral history of the region by the Italian historian Alessandro Portelli. (He notes in the introduction that the particular kind of outsider he was was helpful in building trust with his narrators: better rural Italy than New York, for sure). At one point in the book, there’s a discussion about whether Kopple’s cameras made a difference: if the scabs and sheriffs were less likely to shoot knowing it was being recorded. The class consensus was skeptical. It made me think about the road since 1992, when a single camcorder video of police brutality was the kickoff to an uprising, through the countless videos that helped spur Black Lives Matter and the terrible realization of the last year and a half that having a genocide livestreamed may turn people against it but is powerless to stop it. *

I was teaching the movie because I’ve been trying to structure my composition classes largely around interviewing and oral history - partly, yes, as a way around the thing, but also for what it does: how it helps the quieter ones talk and the louder ones listen, how it tunes people in to the nuances of speech and creates a terrain on which students can actually have the experience of creating original artifacts and knowledge rather than a simulacrum of academic work.**

On another level, I’ve been thinking about oral history as a form of truth telling and meaning-making. As I was talking to students about Harlan County, folks were in the streets in L.A. fighting against thugs with a level of power, brutality and impunity the coal companies could only dream about. I wanted students looking at the news to notice what Ken Klippenstein pointed out, how many of the piece on the protests didn’t bother to interview a single protestor.

When I asked students about the film, they all said the scene that struck them the most was when Lawrence Jones, a well-liked young miner with a 16 year old wife and baby, was killed and that pushed the miners and the company both to settle. Students weren’t shocked when one miner’s wife pulled a gun from her bra, though it did catch their attention. I thought about this when I read the expected pearl-clutching about burning cars. (If sabotaging the gestapo’s vehicles is violence, take it up with the nuns in the Sound of Music). And still, the idea that one death could shock events into shape felt so sadly quaint.****

Meanwhile, in my Creative Nonfiction class, we were talking about truth telling in a different way. To be honest, I haven’t been sure how to handle my fascism/work balance in the classroom this semester. To ignore the reality of where we are feels like evasion, but if you just come in screaming or wanting to commiserate about the headlines, you’re not really serving anyone. And what I’ve learned is that this time around, folks aren’t shut down but they are scared and you’re not going to have a good discussion until you’ve built some trust. In this class, a lot of the conversation was about what it means to write nonfiction, to write the truth or write truthfully, and the obstacles. The obstacles could be censorship, but also wanting to please your parent or your teacher, or being worried about your grade, or feeling embarrassed about what you want to write about, or feeling that you don’t know enough and don’t know how to learn enough. Endless reasons.

The most fascinating discussion of the semester happened when we talked about Kiese Laymon’s interview with Jennifer Baker about these obstacles, “Is It Possible to Write a Truthful Memoir.” Baker notes that Laymon starts his masterpiece of a memoir Heavy by stating “I wanted to write a lie.” Meaning he wanted to write things the way he wishes they had been, or in a way to please his mother. The part of the interview we kept coming back to was this:

I don’t know what truth actually is, but I know what honest attempts at reckoning are. I’m not saying I’m writing honesty, I think I’m attempting to honestly reckon, which is the difference. At the end of that honest reckoning, maybe some people might call it truth. I wouldn’t call it truth but I would call it an attempt. I think sometimes we know when we’re honestly attempting to reckon, honestly attempting to remember, honestly attempting to render. As opposed to when we’re attempting to manipulate. And even in those honest attempts it can be full of lies.

I kept using that phrase in the class after that, an honest reckoning. When a class is going well, like when a standup routine is going well, it can have callbacks. We need writers to tell the truth in a time of lies! always feels a little daunting and overblown and awkward, not only because every blowhard online who did their little part to get us into this mess talks about telling truth in a time of lies, and a few of them may actually believe it. An honest reckoning - one that explores self-doubt, self-pity and our complicities small and large - feels in this way not a lesser goal than Truth, not even a more manageable one, but a higher one, in so far as it is the only kind I believe possible or desirable.

Here are some truth-reckoning pieces I’ve been spending time with recently:

A beautiful tribute to the WTF podcast as it comes to a close. I think Maron is a great exemplar of honest reckoning, especially in how he’s spoken about his own shit, including addiction and especially his reckoning with #metoo and cultural shifts and how, instead of retreating into grumpiness or outright reaction at these new cultural voices, he let it open up his soul to new voices and kinds of expression. I’m not usually a comedy head, but Maron convinced me that as it is one pathway by which to make the art of self-examination bearable, it’s an important art form.

My friend Briallen with a beautiful meditation on the meaning of sanctuary.

It’s been ten years since the system murdered Kalief Brower for insisting on his innocence and his rights and for not having $3000. Bronx Community College, where he was a brilliant student, has a scholarship for formerly incarcerated students in his memory.

This piece by Mohammed Mhawish, whose substack you should you should read, got to me - it’s not just that Ms. Rachel speaks out, it’s what her humanity embodies that they are at war with.

At n+1, Liv Veazey, who I was lucky enough to work a little with on oral history curriculum building, has the best thing I’ve read about the cruel absurdities of our monstrous immigration system, from the perspective of someone bearing witness and offering support.

This piece, also at n+1 about attending an ICE/CBP recruiting fair also really hit me. Something I think about all the time is complicity. A lot of people talk about being raised on Holocaust stories that were manipulated in certain ways to make you a Zionist, and about how taking in these messages can also make you an anti-Zionist real quick if you think about them at all. For me, though, the thing that stuck most was the categories that Art Spiegelman uses in Maus - perpetrator, victim and bystander. A lot of the curriculum and discussion was about the bystanders - why were they not more courageous? Why did they claim not to know? A lot of the questions repeatedly raised in anguish during the genocide assume that we are and are talking to bystanders. (“You can’t claim not to have know.” “Wonder what you would have done in the Holocaust? You are doing it now.”) Sometimes we talk about complicity, realizing that, through out tax dollars, we are the perpetrators.

Now that the fascists are even more directly right in front of us, the question of the perpetrators seems more urgent and strangely missing or displaced. When people see that the thugs have unmarked cars, face masks, and no badges, they say “We don’t even know who these people are!” It’s an interesting reaction to me. Of course, masked men and unmarked cars visualize the reality of our fascist moments in ways it’s hard not to react to. But in another sense, we do know who they are. They’re ICE. At the margins, there are certainly people taking advantage of the moment for some freelance terror, but the idea that the masked thugs might be “imposters” strikes me as a major cope, as the kids say.

But on another level, I think this reaction points us to something important. When we say “who are they,” we mean, who might try to do this kind of work? Over at n+1, a writer with the truly genius pseudonym Yanis Varourfuckice spent a few days talking to people at an ICE/CBP recruiting fair and found people who are bored, hate their shitty jobs, like to travel and see the great outdoors:

One of the ICE applicants I spoke with seemed to have an insatiable desire for conflict in line with this hypothesis. All his life, he said, he had hoped to fight wars in Iraq or Afghanistan. He’d joined the army hoping to fulfill this desire. But our foreign wars had wound down by the time of his enlistment, and he never got a chance to fight abroad.

Or:

A longtime ICE agent said he had accompanied undocumented immigrants on deportation flights to more than fifty countries and stayed in numerous three- and four-star hotels. A White House rooftop sniper said that she had had “amazing experiences in foreign countries” and that the camaraderie of her sniper team reminded her of her college volleyball team.

There are strategic lessons here about what kind of opposition to ICE might make these folks feel their job choice was less of a fun romp. But also, I wonder, what kind of reckoning will we do with the fact that these are the humans our culture/society/nation/lifeworld has produced?

* I continue to think obsessively about the fact that while the sense that “no one cares” about the genocide is understandable, the real picture is in some ways harder: millions care, but we have a democracy crisis that predates Trump that makes it almost impossible for people to have their desires reflected in what the government does, especially when it comes to war. This does not mean that the parties are the same, but it does mean that more and more people will feel as if they are, which in turns reinforces the nihilism which only serves the fascists. Not good!

** On this note, I’m really proud of this article that my friend and colleague Kristen and I wrote about “non-fake” writing assignments that engage students; it’s not about the thing but a good place to start if you are worried about it.

*** By pure coincidence, Lawrence Jones was killed the day I was born, fifty years ago last August. It was also the same year Studs Terkel wrote his masterpiece on Americans at work.